“The point of my work is my own physical engagement with the world in different ways, whether it’s walking, or making fingerprints, or throwing stones.” – Richard Long

In August of last year, I spent a week solo hiking in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Near the end of my trip, I hiked 5 miles of boulder fields completely cloaked in fog. I felt as though a nomadic explorer, lost in some other-world because all I could see at any point in time was a wall of grey mist that occasionally parted to reveal a short glimpse of the trail, arm’s length in reach.

I have no idea what I hiked through that day, I imagine the experience is similar to Gianni Motti’s 6-hour long walk through the Large Hadron Collider, a 17-mile long underground particle accelerator tunnel:

“After 2 kilometers, I lost all notions of time and space. I don’t remember anything, I was elsewhere.” – Gianni Motti

Walking, it turns out, is beautiful.

Walking also touches on my many aspects of art-making including Generative Art, Instruction Art, Culture Jamming and Data Art.

The Situationists (1950′s – 1970′s) developed the concept of “psychogeography,” decoding urban space by moving through it in unexpected ways. The Situationists also promoted the idea of “detournement,” creating new work out of previous media work that is antagonistic or antithetical to the original work. (This concept reminds me of my corporate motto mashups.)

Artists explore walking as a way to increase consciousness and perception, challenge authority and elitism, explore perception of reality and critique political and social agendas through mashups, collage, detournement and psychogeography.

“For us, art is not an end in itself..but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in.” - Hugo Ball of the DADAists

In 1970, Trisha Brown staged “Man Walking Down the Side of A Building,” which was recreated at the Tate Modern in 2006. This piece turns on it’s head the concept of what a walk is, and where it is to be performed (vertically, no less):

“Natural activity under the stress of an unnatural setting. Gravity reneged. Vast scale. Clear order. You start at the top, walk straight down, stop at the bottom.” – Trisha Brown

Executing a walk takes many forms, including using artist protocols to determine the walk. The simplest walking protocol involves executing a recognizable figure in the landscape:

A line is “one of the more sparse, singular expressions of oneness.” -La Monte Young

Walks also make use of materials on hand (bricolage) to create the work. In Tour de Fence by Kayle Brandon and Heath Bunting, climbing fences becomes a humorous, but pointed way to reclaim public space from private encroachment:

“tour de fence is the answer to your real needs. while the internet promised to level out all barriers, tour de fence enables you to surmount the fences out there that people erect to obstruct your way every day.”

One of the earliest examples of Instruction Art is Tristan Tzara’s recipe for a poem, which was meant to undermine the idea of the Artist as Creative Genius. The instructions mocked art world elitism by showing how easy it could be for anyone to produce an original work of art. Later artists such as Sol LeWitt created Instruction Drawings to make art that no longer depended on the skills of a craftsman.

If-Then Procedural Walks continue this tradition of procedural art and are also examples of primitive Generative Art – artwork carried out by rules. William Hou Je Bek, who creates algorithm-generated walks, believes “code illustrates the performative aspects of language.” Using computers to generate algorithmic art gives us, “so much new information about humans, about what makes up intelligence, and about how little we understand of ourselves.”

Other artists create walks as mazes to encourage getting lost and promote, “the disorientation that furthers adventure, play, and creative change.” Upon getting lost in her own labyrinth maze, Yoko Ono reflected:

“In life, you think you can do whatever you please, because the obstacles are invisible. Eventually you always stumble into something and realize that the direction was forbidden or not possible.” – Yoko Ono

With the rise of new technologies such as GPS and Radio Identification Frequency Tags, locative media projects were born. Locative Media projects can be thought of as “annotative: virtually tagging the world, or phenomenological: tracing the action of the subject in the world.” Artists like Jeremy Wood use GPS to draw and write on the landscape creating “visual journals that document a personal cartography.”

“Seeing the rhythms and patterns of one’s tracks can have the effect of seeing your own ghost. The qualities of line in GPS drawings can reveal a great deal about movement and process…GPS drawings can detail the elegant lines of a railway and a squiggly walk to the local shops…The speed of travel can also be colored to indicate the cold blues of slow dithering to red hot top speeds, and the altitude of tracks can add pressure and depth of line.” -Jeremy Wood

Jeremy Wood walked for 17 days accumulating 238 miles of GPS tracks to make a campus map of the University of Warwick (“Traverse Me”, 2010.)

GPS data can be rendered, sculpted and animated. Other similar projects include “Amsterdam Real Time” which follows the paths of 10 participants traveling around Amsterdam, and Teri Rueb’s “The Choreography of Everyday Movement,” a sculptural-GPS mapping project.

Traditional mapping projects seek to locate data in geographical space. What happens when we no longer care about longitude and latitude and seek to transpose and map this data in new ways?

In “Shadows from Another Place: San Francisco <—> Baghdad “(2004), Paula Levine transposes mapping data of missile and bomb strikes in the Iraqi capital to the city of San Francisco. This transposing of data from one geographical location to another hearkens back to The Situationists:

“Any elements, no matter where they are taken from, can serve in making new combinations…when two objects are brought together, no matter how far apart their original contexts may be, a relationship is always formed… The mutual interference of two worlds of feeling, or the bringing together of two independent expressions, supersedes the original elements and produces a synthetic organization of greater efficacy.”

(However, in today’s day and age, cultural jamming as advocated by The Situationists has lost is cultural edge, the techniques incorporated into publicity campaigns, Flashmobs just another marketing tool.)

Walking as an art form can also take the form of oral history to capture the stories of a city, projects such as Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood in NYC, and [murmur] in Toronto, and City of Memory by Local Projects – a dynamic map of New York City stories designed by ITP-alum Jake Barton.

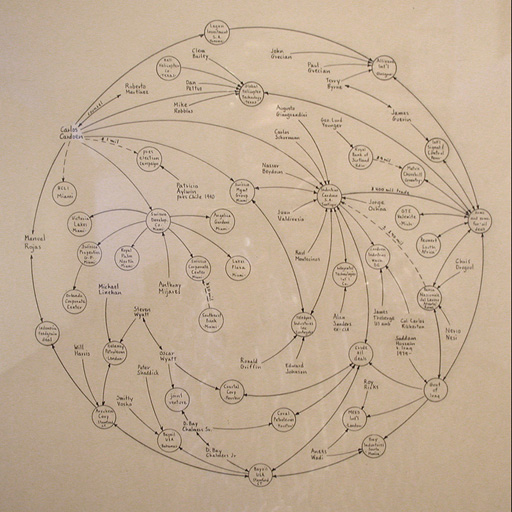

Many artist mapmaking projects also have political goals and aim to reveal “the presence, behind a given situation, of forces that were hidden until then.” Mark Lombardi created pencil drawings that visualized crime and conspiracy networks as told to him by those deep in the field.

Other projects that use Data Visualization to map power relations include “They Rule” by Josh On and FutureFarmers which shows the interlocking network of members of Boards of Directors of the top 500 companies in the US.

Lastly, artists explore walking and mapping in the context of surveillance, exploring art-making not as “a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.” We now live in a “control society” where we are filmed by CCTV cameras, and our personal activity (cell phone usage, purchase history) is stored in databases.

ISee maps surveillance cameras in Manhattan to allow users the ability to chart paths of “least surveillance.” The New York Surveillance Camera Players purposely performed plays and skits in front of surveillance cameras monitored by the NYPD leading to frequent shut-downs of the performances. After Hasah Elahi was detained and questioned by the FBI as a potential terrorist, he began an ongoing “self-surveillance” project posting his location, and photographs of his daily, normal cultural activity online. In Evidence Locker, Jill Magrid collaborates with the operators of Liverpool’s CCTV cameras to initiate surveillance of herself as she traveled through Liverpool for 30 days.

“Self-surveillance is a way of seeing myself, via technology, in a way I could not otherwise.” -Jill Magrid

Lastly, surveillance touches on issues of borders between countries. In BorderXing, Heath Bunting crossed 24 borders between countries in Europe by foot without passport or visa to gather data on clandestine border crossing, then posted the information online.

Natalie Jermijenko uses new technologies in the hope of helping social transformation. Her best known project is OneTrees, in which she planted 20 genetically identical trees in neighborhoods of San Francisco. How well (and differently) the trees grow in each neighborhood shows the health and pollution of the area.

“If you undertake a walk, you are echoing the whole history of mankind, from the early migrations out of Africa on foot that took people all over the world. Despite the many traditions of walking–the landscape walker, the walking poet, the pilgrim – it is always possible to walk in new ways.” -Richard Long

This blog post explores research and concepts written about in much greater detail in “Walking and Mapping” by Karen O’Rourke. Diana Freed and I are creating an artist mapping project that explores ideas and concepts touched upon in “Walking and Mapping.” Read more about the project in this earlier blog post.